“By 2050, there will be more plastic in our oceans than fish”

Greenbatch, from the 2016 World Economic Forum

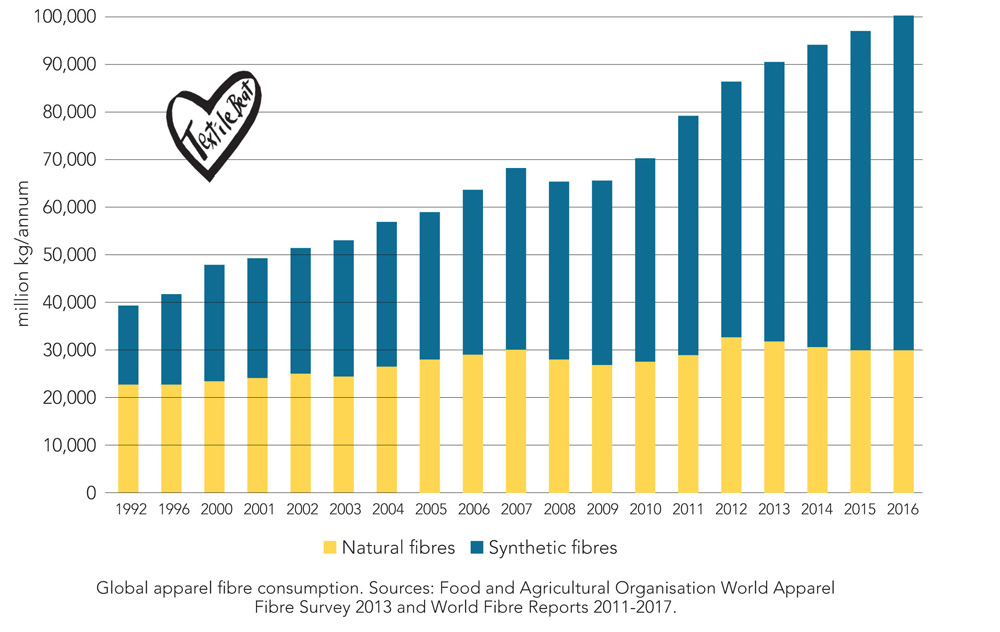

The quote that started it all. Darren Lomman, Engineer, Social Innovator and Greenbatch CEO and Founder, was astounded to find out that a whole 0% (zilch, nada) of Western Australia’s plastic was reprocessed in WA when he first heard this quote back in 2016. Yeah, you heard that right, none of the plastic that you put in the recycling bin was being recycled here, or even in Australia for that matter. Rather, it was packaged up and sold to other countries for them to deal with. And that is only the portion of plastics that made it to the recycling bin in the first place – a lot doesn’t there and end up in landfills or the ocean!

So yeah, we have a plastic problem (or crisis), Darren wasn’t having a bar of it and so Greenbatch was born.

Before Greenbatch grew to the social enterprise that it is today (in just a few years), it was one guy (shredding bottles with scissors and an office paper shredder) with a drive to do something about a pretty important environmental issue.

But other countries have been recycling plastic for years, what makes this socially innovative?

Well Obama,

“Social innovation is the process of developing and deploying effective solutions to challenging and often systemic social and environmental issues in support of social progress.”

Stanford Graduate School of Business

I think Greenbatch achieved this in 2 ways…

One. Instead of trying to convince the government or investors to build a hugely expensive plastic recycling facility (which will eventually be needed), how about starting with partnerships and getting the public on board? So instead of being something that people have to do to follow government regulations, it becomes something they want to do. The beginning of project was crowd-funded, and they managed to raise $70,000 in 4 weeks with the help of social media.

Two. If you’re going to start recycling plastic, you’ve got to have an idea of what you’re going to recycling it into. Well, did you know that about 70% of our high schools have 3D printers? I didn’t, but Greenbatch did (or at least found this out) and they tapped into this. So they’re partnering with schools (now over 70 schools in Perth!). Getting school kids and teens on board to learn about the need for recycling. Greenbatch goes to the school to give them information about plastic waste, the schools collect plastic bottles, give them to Greenbatch and then will be able to use the 3D printer filament made from their bottles to create and learn whilst also learning the need for action to protect the future environment. Neat right? I love the idea. And it’s not just me who loves it, companies have jumped at the chance to partner with them and now the public come in droves on open days to deliver plastic that they want to see recycled here in Perth. They have plans to eventually recycle plastics into other products but it’s such a good idea to kick off in this way.

And, like you heard in my vlog, they’re partnering with other organisations to make this possible (like Engineers Without Borders, wooo!). Engineering companies have partnered by way of pro bono engineering and engineering students can volunteer with Greenbatch to get experience and work on a real project. The organisation also relies on community volunteers to sort plastics and collect plastics from events.

It’s pretty easy to see approaching this issue in this way can work towards the SDGs in more ways then one. I’ll start with the most obvious, the end goal is increasing recycling in our society and moving towards (slowly) a circular economy which is so critical when considering Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production. If you think back to that quote I started with, working towards preventing plastics ending up in our oceans is important for Goal 14: Life Below Water. And of course, all that pollution comes from the land so we can’t forget Goal 15: Life on Land. This is an approach that includes groups in society partnering together….Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals! We can’t forget the positive impact this has on educating the community (Goal 4: Quality Education) and working towards sustainable cities and communities (Goal 11). And lastly, this type of project is using innovation to work toward developing the recycling industry here in WA (Goal 9!).

Woah, talk about 2 bird with one stone or…7 SDGs with one social innovation! Not only is Greenbatch paving the way for plastic recycling in WA, they are doing it in a really cool and socially innovative way. But, could an initiative such as this help advance the agenda of wastewater treatment and recycling?

Yes!

But how?

Well I think there is definitely room for a social innovation project to sweep in to get people talking, learning and caring about wastewater. But I think the really cool thing about Greenbatch that could be applied to social innovation for wastewater problems is the partnerships for success. Particularly the ones with schools! Water and recycling are often kept separate when we learn about them but there needs to be the connection between them! Hands on activities in schools that get kids caring about wastewater are important and then that’s a discussion that comes home with them.

Wouldn’t it be awesome if all schools (or like a group of schools) could create and build a demo sustainable house like a mini Josh’s House that integrates water reuse and energy efficiency? What about engineering students volunteering to get work experience with engineers working pro-bono to develop it? Or sustainable classrooms where water from the taps in classrooms (usually only used for washing hands) could be used for watering a garden in the school. That would really start a discussion within the school and in the community and I think that’s kinda what we need. There are a lot of issues faces wastewater treatment and recycling that could be address by improved education on it. But also, by encouraging learning about wastewater and gaining the interest of society, larger-scale technological approaches can be implemented with acceptance and enthusiasm by the public.